2021 The Year of Napoleon

Why was the Pope held captive in Fontainebleau?

Date of publication of the page and author of publication

Created the: - Updated:

After Napoleon's coronation in Notre-Dame de Paris on 2nd December 1804, relations with the pontiff soon deteriorated, as the Emperor had repeatedly violated the sovereignty of the Roman states by imposing his policy of continental blockade.

The conflict between the heads of state turned into a religious crisis when Pope Pius VII refused to give canonical investiture to new archbishops and bishops, leaving France with vacant episcopal sees and worshippers without a pastor.

Initially a latent crisis, it broke out in 1809 when Napoleon, in retaliation, decided to annex the Papal States and to imprison the pontiff in Savona.

"Non possiamo, non dobbiamo, non vogliamo | We cannot, we must not, we do not want to."

In response, the head of Christendom excommunicated Napoleon, who did his best not to publicise the affair. However, bishops and worshippers wondered whether, in good conscience, they could continue to support an emperor who had been banished from the Christian community. And wondered whether the new Constantine, father of the Concordat, was not somewhat of... a new Attila.

Napoleon eventually called a council which met in the summer of 1811 under the chairmanship of his uncle Cardinal Fesch, Archbishop of Lyons, to try and 'put an end to the scandalous struggles between the spiritual and the temporal for good'. The Emperor of the French actually intended to have his excommunication invalidated and the dissolution of his marriage to Josephine and his new union with Marie-Louise officially recognised by the Pope.

The prelates started to panic at the idea that the head of the Vatican might be attacked and tried to find a solution to the conflict, but this led nowhere, except in further alarming the faithful. The official propaganda tried to hush up the latent religious crisis, but it poisoned the last years of the Empire, gradually awakening opposition to the regime in the form of pamphlets, libels and inflammatory preaching by rebellious priests. Bourbon supporters were also increasingly active at the end of the era, trying to mobilise more supporters against the Usurper.

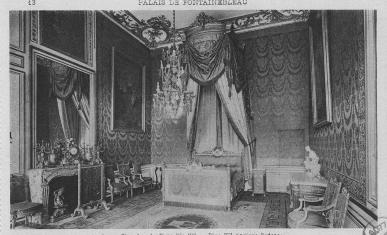

Twelve bishops were sent to Savona in August 1811, however Napoleon knew their conciliatory mission would come to nothing. Pope Pius VII made them wait until February 1812, pretending he was either reflecting or hesitating. Before leaving for the Russian campaign, Napoleon decided to bring the Pope back to France, still hoping that he would change his mind and agree to sign a new Concordat. Following a long, arduous journey, the pontiff was secretly transferred to the Château de Fontainebleau in June 1812, where he would remain captive for nearly 18 months.